What You Will Learn

After reading this note, you should be able to...

- This content is not available yet.

Definition:

Endometriosis refers to a condition in which endometrial-like tissues or stroma are found in locations other than the uterine lining.

Adenomyosis is reserved for endometrial-like lesions within the myometrium (Previously endometriosis interna).

.jpg)

Epidemiology:

Affects all races though seen more in whites

Found almost exclusively in women of reproductive age

Rare in pre-menarche and post-menopausal women

Smoking, exercise and use of OCPs (current and recent) may be protective

Risk factors:

Age

Race

Low parity

Familial tendency

Early menarche / late menopause

High estrogen

Environmental Factors like pollutants

.png)

Prevalence:

Present in 20-45% (infertile) & 1-5% (fertile) women

Population based studies: 6.2 - 7.9%

Epidemiology studies: 0.25 new cases /1000 WY

Late diagnosis:

Several studies have reported large diagnostic delays in endometriosis.

10.4 years in Germany and Austria (Hudelist, et al., 2012).

8 years in the UK and Spain (Ballard, et al., 2006, Nnoaham, et al., 2011).

Reasons for diagnostic delay

- Intermittent use of contraceptives causing hormonal suppression of symptoms

- Misdiagnosis

- Attitude towards menstruation

- Normalisation of pain by the women, their mothers, health workers, gynecologists or other “specialists”

Making a diagnosis

- Symptoms

- Signs

- Findings on Investigations

Overall, the evidence on symptoms/signs that indicate a diagnosis of endometriosis is weak and incomplete.

Symptoms

Reproductive tract:

- Spasmodic dysmenorrhoea

- Lower abdominal pain, lower back pain

- Menstrual disorders

- Deep dyspareunia

- Infertility

- Cyclical vulval pain

Urinary tract:

- Cyclical dysuria

- Hematuria

- Ureteric obstruction (loin pain)

GIT:

- Dyschezia

- Cyclical rectal bleeding

- Hematochezia

- Cyclical pain/bluish swelling/bleeding of abdominal scars

Lung:

- Cyclical

- Hemoptysis

- Catamenial pneumothorax

- Pleural effusion

CNS:

- Catamenial seizures

- Headache

MSK:

- Limb pain

- Sciatica

Key symptoms

Dysmenorrhea

Infertility

Dyspareunia

Post-coital bleeding

Presence of ovarian cyst

Irritable bowel syndrome

Chronic pelvic pain

According to Bellelis, et al., 2010:

- Dysmenorrhea was the chief complaint, reported by 62% of women

- Chronic pelvic pain was 57%

- Deep dyspareunia 55%

- Cyclic intestinal complaints 48%

- Infertility 40%

- Incapacitating dysmenorrhea 28%

Signs

There may be no signs

The tissues may be found in scars

Abdominal tenderness may be noted

Pelvic examination may show—

- Perineal, vaginal and cervical lesions

- Tender nodules may be palpated in rectovaginal septum and uterosacral ligaments

- Adnexal tenderness, and masses may be noted

- Uterus may be fixed or retroverted

- Tender, nodular or boggy pouch of Douglas

Findings most reliable when examination is performed during menstruation

.png.jpg)

Recommendations:

Consider the diagnosis of endometriosis in the presence of gynecological symptoms such as: dysmenorrhea, non-cyclical pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, infertility. (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

Clinicians should consider the diagnosis of endometriosis in women of reproductive age with non-gynecological cyclical symptoms (dyschezia, dysuria, hematuria, rectal bleeding, and shoulder pain). (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

Clinicians may consider the diagnosis of deep endometriosis in women with (painful) induration and/or nodules of the rectovaginal wall found during clinical examination, or visible vaginal nodules in the posterior vaginal fornix (Bazot, et al., 2009). (Grade of recommendation: C).

Clinicians may consider the diagnosis of ovarian endometrioma in women with adnexal masses detected during clinical examination. (Grade of recommendation: C).

Clinicians may consider the diagnosis of endometriosis in women suspected of the disease even if the clinical examination is normal (Chapron, et al., 2002). (Grade of recommendation: C).

- Laparoscopy

- Histology

- Ultrasound [TVS]

- MRI

- Biomarkers

Laparoscopy with histology is diagnostic.

Uterine Fibroid growth is estrogen dependent.

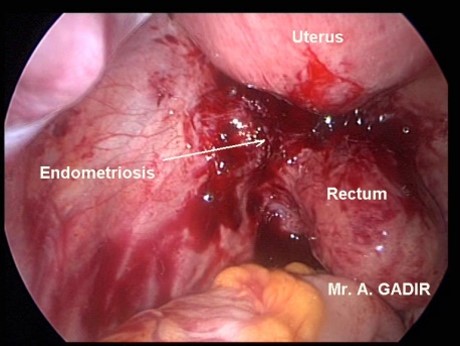

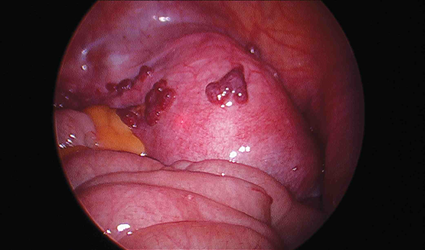

Laparoscopy

Gold standard.

The combination of laparoscopy and the histological verification of endometrial glands and/or stroma is considered to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of the disease.

- Accuracy depends on surgeon

- Systematic inspection of pelvis required

- Document type, location and extend of all lesions

- Histologic confirmation is a good practice

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Staging:

- Stage 1 (minimal): 1-5

- Stage 2 (mild):6-15

- Stage 3 (moderate):16-40

- Stage 4 (severe): >40

.png)

Recommendation:

That clinicians perform a laparoscopy to diagnose endometriosis, although evidence is lacking that a positive laparoscopy without histology proves the presence of disease. (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

Histology

Ovarian Endometrioma

That clinicians obtain tissue for histology in women undergoing surgery for ovarian endometrioma and/or deep infiltrating disease, to exclude rare instances of malignancy. (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

Transvaginal USS

In women with symptoms and signs of rectal endometriosis, transvaginal sonography is useful for identifying or ruling out rectal endometriosis (Hudelist, et al., 2011). (Grade of recommendation: A).

Clinicians are recommended to perform transvaginal sonography to diagnose or to exclude an ovarian endometrioma (Moore, et al., 2002).

- Ground glass echogenicity

- One to four compartments

- No papillary structures with detectable blood flow.

(Grade of recommendation: A).

MRI

Clinicians should be aware that the usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to diagnose peritoneal endometriosis is not well established (Stratton, et al., 2003).

- 90% sensitivity and specificity not supported by recent review

- Superior to ultrasound

- May be used to monitor prognosis

(Grade of recommendation: D).

Clinicians are recommended not to use immunological biomarkers, including CA-125, in plasma, urine or serum to diagnose endometriosis (May, et al., 2010, Mol, et al., 1998). (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

Women with endometriosis are confronted with one or both of two major problems- endometriosis associated pain and/or infertility.

Pain

Pain is generally premenstrual and mostly due to

- Adhesions with traction on tissues

- Nerve entrapment, pressure symptoms

- Bradykinin and PG release especially PGF

- Site and depth of implants

Severity of pain does no correlate to severity of disease

Infertility

No agreement on the mechanism in minimal and mild disease.

Altered peritoneal fluid and contents seem to be implicated.

- Ovarian function – endocrinopathy – anovulation. Rate of ovulation is reduced by 11-27% - nearly ½ get pregnant when this is corrected.

- Coital function— dyspareunia causing decrease frequency of coitus and reduced penetration

- Tubal function— PG alters tubal & cilial motility. Impaired fimbrial activity.

- Sperm function— phagocytosis, inactivation by antibodies.

- Endometrium— Implantation defects

- Early pregnancy failure— Increased early abortion & PG induced immune reaction

Medical treatment

Endometriosis associated Pain

- Use of NSAIDS

Clinicians are recommended to prescribe hormonal treatment for endometriosis associated pain.

- Hormonal contraceptives (level B)

- Progestogens (level A)

- Anti-progestogens (level A)

Or

- GnRH agonists (level A)

Clinicians should take patient preferences, side effects, efficacy, costs and availability into consideration when choosing hormonal treatment for endometriosis-associated pain. (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

Combined oral contraceptives

Clinicians can consider prescribing a combined hormonal contraceptive, as it reduces endometriosis-associated dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pain (Vercellini, et al., 1993).

Clinicians may consider the continuous use of a combined oral contraceptive pill in women suffering from endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea (Vercellini, et al., 2003).

Progestogens

Clinicians are recommended to use progestogens [medroxyprogesterone acetate (oral or depot), dienogest, cyproterone acetate, norethisterone acetate or danazol] or anti-progestogens (gestrinone) as one of the options, to reduce endometriosis-associated pain (Brown, et al., 2012). (Grade of reccomendation: A).

GNRH agonist

Clinicians are recommended to use GnRH agonists (nafarelin, leuprolide, buserelin, goserelin or triptorelin), as one of the options for reducing endometriosis-associated pain, although evidence is limited regarding dosage or duration of treatment (Brown, et al., 2010). (Grade of recommendation: A).

Clinicians to give careful consideration to the use of GnRH agonists in young women and adolescents, since these women may not have reached maximum bone density. (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

Add Back

Clinicians are recommended to prescribe hormonal add-back therapy to coincide with the start of GnRH agonist therapy, to prevent bone loss and hypoestrogenic symptoms during treatment. (Grade of recommendation: A).

The rationale for add-back is based on the 'estrogen threshold hypothesis'. Endometriotic tissue growth is stimulated by estrogen. Low circulating E2 concentrations cause regression of estrogen-sensitive tissues like endometrial implants. Adding back small amounts of hormone (estrogen or estrogen plus progesterone) increases circulating E2 levels enough to maintain bone integrity and prevent menopausal symptoms while suppressing other tissues, like the endometrium.

Surgical treatment

For endometriosis associated pain

Laparoscopy preferred to open surgery

- Elimination of endometriotic lesions

- Division of adhesions

- Interruption of nerve pathways

- Hysterectomy with BSO

See and treat:

When endometriosis is identified at laparoscopy, clinicians are recommended to surgically treat endometriosis, as this is effective for reducing endometriosis-associated pain i.e. ‘see and treat’ (Jacobson, et al., 2009). (Grade of recommendation: A).

Recommendation:

Clinicians clearly distinguish

- Adjunctive short-term (< 6 months) hormonal treatment after surgery. from

- Long-term (> 6 months) hormonal treatment; the latter is aimed at secondary prevention.

Clinicians should not prescribe adjunctive hormonal treatment in women with endometriosis for endometriosis-associated pain after surgery, as it does not improve the outcome of surgery for pain (Furness, et al., 2004). (Grade of recommendation: A).

The GDG states that there is a role for prevention of recurrence of disease and painful symptoms in women surgically treated for endometriosis.

The choice of intervention depends on patient preference, cost, availability and side effects. For many interventions that might be considered here, there are limited data. (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

LUNA

Clinicians should not perform laparoscopic uterosacral nerve ablation (LUNA) as an additional procedure to conservative surgery to reduce endometriosis-associated pain (Proctor, et al., 2005). (Grade of recommendation: A).

PSN

Clinicians should be aware that presacral neurectomy (PSN) is effective as an additional procedure to conservative surgery to reduce endometriosis-associated midline pain, but it requires a high degree of skill and is a potentially hazardous procedure (Proctor, et al., 2005). (Grade of recommendation: A).

Hormonal treatment

In infertile women with endometriosis, clinicians should not prescribe hormonal treatment for suppression of ovarian function to improve fertility (Hughes, et al., 2007). (Grade of recommendation: A).

Early laparoscopy

In infertile women clinicians can consider operative laparoscopy, instead of expectant management, to increase spontaneous pregnancy rates (Nezhat, et al., 1989, Vercellini, et al., 2006a). (Grade of recommendation: B).

Adjunctive hormone treatment

In infertile women with endometriosis, clinicians should not prescribe adjunctive hormonal treatment after surgery to improve spontaneous pregnancy rates (Furness, et al., 2004). (Grade of recommendation: A).

Endometriosis and ART

Use of assisted reproductive technologies for infertility associated with endometriosis is recommended, especially if tubal function is compromised or if there is male factor infertility, and/or other treatments have failed. (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

IUI with COS

In infertile women, consider performing intrauterine insemination with controlled ovarian stimulation within 6 months after surgical treatment, since pregnancy rates are similar to those achieved in unexplained infertility (Werbrouck, et al., 2006). (Grade of recommendation: C).

IVF/ICSI

Recommends the use of assisted reproductive technologies for infertility associated with endometriosis, especially if tubal function is compromised or if there is male factor infertility, and/or other treatments have failed. (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

GNRH prior to ART

Clinicians can prescribe GnRH agonists for a period of 3 to 6 months prior to treatment with assisted reproductive technologies to improve clinical pregnancy rates in infertile women with endometriosis (Sallam, et al., 2006). (Grade of recommendation: B).

Menopause and Endometriosis

In postmenopausal women after hysterectomy and with a history of endometriosis, avoid unopposed estrogen treatment.

However, the theoretical benefit of avoiding disease reactivation should be balanced against the increased systemic risks associated with combined estrogen/progestogen or tibolone. (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

In women with surgically induced menopause because of endometriosis, estrogen/progestagen therapy or tibolone can be effective for the treatment of menopausal symptoms (Al Kadri, et al., 2009). (Grade of recommendation: B).

Endometriosis and Cancer

There is no evidence that endometriosis causes cancer.

There is no increase in overall incidence of cancer in women with endometriosis,

Some cancers (ovarian cancer and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) are slightly more common in women with endometriosis. (Grade of recommendation: GPP).

Practice Questions

Check how well you grasp the concepts by answering the following questions...

- This content is not available yet.

Send your comments, corrections, explanations/clarifications and requests/suggestions