What You Will Learn

After reading this note, you should be able to...

- This content is not available yet.

Read More 🍪

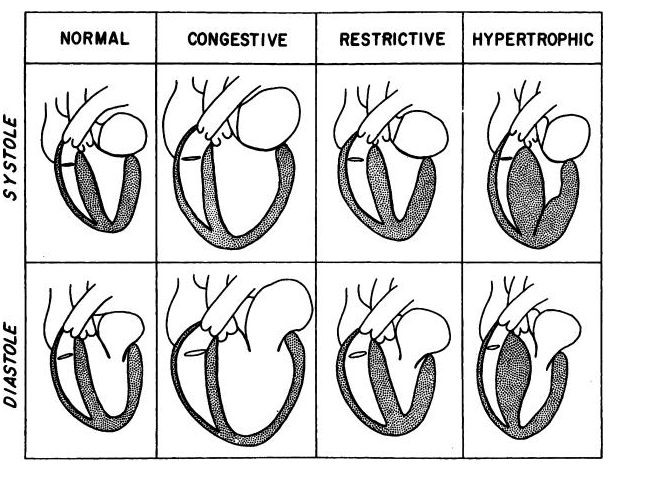

- Primary myocardial disease, or cardiomyopathy, is a disease of the heart muscle itself, not associated with congenital, valvular, or coronary heart disease or systemic disorders.

- It is distinct from the specific heart muscle diseases of known cause.

- Hypertrophic

- Dilated (or congestive)

- Restrictive

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

- Left ventricular noncompaction

- Dilated (or congestive) cardiomyopathy is characterized by:

- Decreased contractile function of the ventricle associated with ventricular dilatation.

- Diastolic dysfunction and systolic dysfunction

- Endocardial fibroelastosis (seen in infancy) and doxorubicin cardiomyopathy (seen in children who have received chemotherapy for malignancies) have clinical features similar to those of dilated cardiomyopathy.

- HCM

- There is massive ventricular hypertrophy with a smaller than normal ventricular cavity.

- Contractile function of the ventricle is enhanced, but ventricular filling is impaired by relaxation abnormalities.

- Diastolic dysfunction

- Dynamic systolic dysfunction

- RCM

- Denotes a restriction of diastolic filling of the ventricles (usually infiltrative disease).

- Contractile function of the ventricle may be normal, but there is marked dilatation of both atria.

Cardiomyopathies

×

![]()

Cardiomyopathies

- Dilated cardiomyopathy is the most common form of cardiomyopathy.

Aetiology

- The most common cause of dilated cardiomyopathy is idiopathic (>60%).

- Familial cardiomyopathy: AD, X-linked, AR, mitochondrial

- Active myocarditis

- Subclinical myocarditis

- Infectious causes other than viral infection (bacterial, fungal, protozoal, rickettsial)

- Endocrine-metabolic disorders (hyper- and hypothyroidism, excessive catecholamines, diabetes, hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, glycogen storage disease, mucopolysaccharidoses)

- Nutritional disorders (kwashiorkor, beriberi, carnitine deficiency)

- Cardiotoxic agents such as doxorubicin

- Systemic diseases such as connective tissue disease

Pathology/Pathophysiology

- There is a weakening of systolic contraction with associated dilatation of all four cardiac chambers.

- Dilatation of the atria is in proportion to ventricular dilatation.

- The ventricular walls are not thickened, although heart weight is increased.

- Intracavitary thrombus formation is common in the apical portion of the ventricular cavities and in atrial appendages and may give rise to pulmonary and systemic emboli.

- Histologic examinations from endomyocardial biopsies show varying degrees of myocyte hypertrophy and fibrosis. Inflammatory cells are usually absent.

Clinical Features

- A history of fatigue, weakness, and symptoms of left-sided heart failure (dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea) may be elicited.

- A history of prior viral illness is occasionally obtained.

Physical Examination

- Palpitation, syncope, and sudden death.

- Features of FTT:

- Dyspnoea, easy fatigability, wheezing, cough

- Pallor

- Altered consciousness

- Hypotension

- Shock

- Signs of CHF (tachycardia, pulmonary crackles, weak peripheral pulses, distended neck veins, hepatomegaly) are present.

- The apical impulse is usually displaced to the left and inferiorly.

- The S2 may be normal or narrowly split with accentuated P2 if pulmonary hypertension develops.

- A prominent S3 is present with or without gallop rhythm.

- A soft regurgitant systolic murmur (caused by mitral or tricuspid regurgitation) may be present.

Investigations

- ECG

- Sinus tachycardia, LVH, and ST-T changes are the most common findings.

- Left or right atrial hypertrophy (LAH or RAH) may be present.

- Atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and atrioventricular (AV) conduction disturbances may be seen.

- Chest X-ray

- Cardiomegaly

- Pulmonary vascular congestion

- ECHO

- E/U/Cr

- ESR

- FBC

Treatment

- Medical treatment

- Is aimed at the underlying heart failure.

- Diuretics (furosemide, spironolactone)

- Digoxin, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (captopril, enalapril) are an integral part of therapy.

- Bed rest or restriction of activity.

- Critically ill children may require intubation and mechanical ventilation.

- Rapidly acting intravenous inotropic support (dobutamine, dopamine) is often needed.

- Use of β-adrenergic blocker therapy in children with chronic heart failure has been shown to improve LV ejection fraction. Carvedilol is a β-adrenergic blocker with additional vasodilating action.

- Antiplatelet agents (aspirin) should be initiated. The propensity for thrombus formation in patients with dilated cardiac chambers and blood stasis may prompt use of anticoagulation with warfarin.

- If thrombi are detected, they should be treated aggressively with heparin initially and later switched to long-term warfarin therapy.

- Patients with arrhythmias may be treated with amiodarone or other antiarrhythmic agents.

- For symptomatic bradycardia, a cardiac pacemaker may be necessary.

- If carnitine deficiency is considered as the cause for the cardiomyopathy, carnitine supplementation should be started.

Prognosis

- Progressive deterioration is the rule rather than the exception. About two-thirds of patients die from intractable heart failure within 4 years after the onset of symptoms of CHF.

- Systemic and pulmonary embolism resulting from dislodgment of intracavitary thrombi occurs in the late stages of the illness.

- Causes of death are CHF, sudden death resulting from arrhythmias, and massive embolization.

- HCM is a heterogeneous, usually familial disorder of heart muscle.

Aetiology

- In about 50% of cases, HCM is inherited as a Mendelian autosomal dominant trait and is caused by mutations in one of 10 genes encoding protein components of the cardiac sarcomere (such as β-myosin heavy chain, myosin binding protein C, and cardiac troponin-T).

- Other cases are sporadic.

- LEOPARD syndrome

- Infants of diabetic mothers

Pathology/Pathophysiology

- The most characteristic abnormality is the hypertrophied left ventricle (LV), with the ventricular cavity usually small or normal in size.

- Although asymmetrical septal hypertrophy, a condition formerly known as idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis, is most common, the hypertrophy may be concentric or localized to a small segment of the septum.

- Microscopically, an extensive disarray of hypertrophied myocardial cells, myocardial scarring, and abnormalities of the small intramural coronary arteries are present.

Pathophysiology

- Subaortic obstruction

- Diastolic dysfunction

- Mitral regurgitation

- Obstruction may vary from moment to moment.

Clinical Manifestations

- History

- Easy fatigability, dyspnea, palpitation, dizziness, syncope, or anginal pain may be present.

- Family history is positive for the disease in 30% to 60% of patients.

- Physical Examination

- A sharp upstroke of the arterial pulse is characteristic (in contrast to a slow upstroke seen with fixed aortic stenosis [AS]).

- A left ventricular lift and a systolic thrill at the apex or along the lower left sternal border may be present.

- Hyperactive precordium.

- The S2 is normal, and an ejection click is generally absent.

- A grade 1 to 3/6 ejection systolic murmur of medium pitch is most audible at the middle and lower left sternal borders or at the apex.

- A soft holosystolic murmur of mitral regurgitation (MR) is often present.

Investigations

- ECG

- The ECG is abnormal in the majority of patients.

- Common ECG abnormalities include left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), ST-T changes, and abnormally deep Q waves (owing to septal hypertrophy) with diminished or absent R waves in the left precordial leads.

- Occasionally, "giant" negative T waves are seen in the left precordial leads, which may suggest apical HCM.

- Other ECG abnormalities may include cardiac arrhythmias and first-degree AV block.

- ECHO

- Chest X-ray

- Urinalysis

- Blood culture

- E/U/Cr

Treatment

- Medical

- Moderate restriction of physical activity is recommended. Patients with the diagnosis of HCM should avoid strenuous exercise or competitive sports.

- Digitalis is contraindicated because it increases the degree of obstruction.

- Prophylaxis against SBE is indicated.

- Clinical screening of first-degree relatives and other family members should be encouraged.

- Annual evaluation during adolescence (12 to 18 years of age) is recommended, with physical examination, ECG, and two-dimensional echo studies.

- A β-adrenergic blocker (such as propranolol, atenolol, or metoprolol) is the preferred drug for symptomatic patients with outflow gradient, which develops only with exertion. This drug reduces the degree of outflow tract obstruction, decreases the incidence of anginal pain, and has antiarrhythmic effects.

- Calcium channel blockers (principally verapamil) may be equally effective in both the nonobstructive and obstructive forms.

- Disopyramide (negative inotropic agent and type IA antiarrhythmic agent) has been shown to provide symptomatic benefit in patients with resting obstruction.

Surgical

- Morrow's myotomy-myectomy. Transaortic LV septal myotomy-myectomy (the Morrow operation) is the procedure of choice for drug-refractory patients with LVOT obstruction.

- Percutaneous alcohol septal ablation.

Prognosis

- Death is often sudden and unexpected and typically is associated with sports or vigorous exertion.

- Sudden death may occur most commonly in patients between 10 and 35 years of age.

- Ventricular fibrillation is the cause of death in the majority of sudden deaths.

- Atrial fibrillation may cause stroke or heart failure.

- In a minority of patients, heart failure with cardiac dilatation ("burned out" phase of the disease) may develop later in life.

- Subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) may affect the mitral valve, at the point of mitral-septal contact, or the aortic valve.

- Incidence increases with age

- Storage disorders

- Infiltrative disorders

Pathology/Pathophysiology

- Normal ventricular dimensions, myocardial wall thickness

- Preserved systolic function

- The most characteristic abnormality is impaired ventricular compliance and filling, and atrial dilatation

Pathophysiology

- Diastolic dysfunction

- Pulmonary hypertension

- PVD

Clinical Manifestations

- History

- Cough, dyspnea, pulmonary oedema

- Dyspnea, palpitation, dizziness, syncope, or anginal pain may be present

- Sudden death

- Physical Examination

- Murmurs are usually absent

- Loud P2

- Gallop rhythm

- Overactive right ventricular impulse

Investigations

- ECG

- Prominent P wave

- RVH

- CXR

- ECHO

Management

- Limited use of drug management

- Cardiac transplantation

- Antiarrhythmic drugs

- Anticoagulants

- Prognosis is poor

Practice Questions

Check how well you grasp the concepts by answering the following questions...

- This content is not available yet.

Read More 🍪

Contributors

Jane Smith

She is not a real contributor.

John Doe

He is not a real contributor.

Send your comments, corrections, explanations/clarifications and requests/suggestions