The Organism

Also known as New World Trypanosomiasis/South American Trypanosomiasis/Mal de Chagas/Chagas-Mazza Disease

American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease) results from infection with the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, a member of the family Trypanosomatidae.

Most strains of this parasite can be classified into two major groups, T. cruzi I and T. cruzi II, which can be separated further into various lineages (e.g., T. cruzi IIa). Lineages tend to be associated with certain host species, although this relationship is not absolute.

T. cruzi is susceptible to many disinfectants. It is destroyed by several hours of exposure to direct sunlight or other harsh environments.

History

In 1907, while working among railroad workers in Brazil, physician Carlos Chagas first became aware of the barbiero, a blood-sucking bug infesting huts of the region. He quickly became interested in the insect and investigated whether it could be a transmitter of any parasites of man.

By 1909, a new species of trypanosome was discovered, and the first published reports followed. Until the 1930s, little attention was given to Chagas disease as a public health issue.

Geographic Distribution

- T. cruzi can be found in the Americas from the U.S. to Chile and central Argentina.

- In the U.S., this parasite is thought to be endemic in approximately the southern half of the country, as well as in California.

- An estimated 8 to 11 million people are infected worldwide.

Populations at Risk

- Chagas disease is most common among people who live in substandard housing in developing areas. Triatomine vectors for T. cruzi are present in the U.S.; however, only a few locally acquired, vector-borne cases have been diagnosed in people.

- The lower prevalence rate in the U.S. is mainly due to higher standards of living and the absence of triatomine species that are well adapted to living in human houses.

- According to the CDC, Chagas is considered a Neglected Infection of Poverty (NIP) in the U.S. since it is found mostly in those with limited resources and limited access to medical care.

- People in certain occupational risk groups may also be exposed; this includes veterinarians, technicians, and laboratory personnel. Individuals who work with wildlife and hunters are at risk, as are travelers to areas where Chagas is endemic.

Species Affected

- Trypanosoma cruzi occurs in more than 100 species of mammals throughout the Americas; infections have been reported among carnivores including dogs and cats, as well as in pigs, goats, lagomorphs, rodents, marsupials, bats, xenarthra (anteaters, armadillos and sloths) and non-human primates.

- In the U.S., opossums, armadillos, raccoons, coyotes, rats, mice, squirrels, dogs and cats are among the most frequent hosts. Birds, reptiles and fish are not susceptible to infection.

Chagas disease is a vector-borne disease transmitted primarily by triatomine insects, which are also called reduviid insects, “kissing beetles/ bugs” or “assassin bugs.”

More than 130 species of these insects appear to be capable of transmitting T. cruzi, with the most important species in the genera Triatoma, Rhodnius and Panstrongylus.

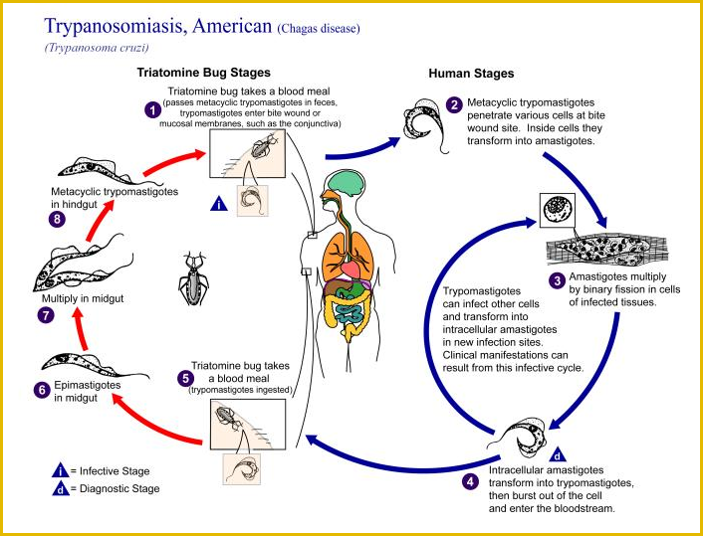

The parasite usually completes its life cycle by cycling between an insect species and a mammalian species with which the insect lives in close association.

.jpg)

There are three basic cycles of transmission for T. cruzi.

- In the sylvatic (wild) cycle, this organism cycles between wildlife and triatomine insects that live in sylvatic environments. Humans and domesticated animals are infected occasionally when they contact these bugs in the wild. The sylvatic cycle is responsible for relatively few cases of Chagas disease. It is the only cycle in the U.S.

- A domestic transmission cycle also exists in Mexico and parts of Central and South America. In this cycle, some insect vectors have colonized primitive adobe, grass and thatched houses, resulting in transmission between humans and insects.

- Transmission cycles between insects and domesticated animals (peridomestic cycles) can also provide opportunities for the parasite to infect humans.

T. cruzi is not spread between mammals by casual contact; however, it can be transmitted directly via blood (e.g., in a blood transfusion) and in donated organs.

Carnivores can acquire this organism when they eat infected prey.

Vertical transmission has been reported in dogs and other animals, both in utero and in the milk. Transmission in milk is very rare in humans, but transplacental transmission can occur at each pregnancy, and during all stages of infection.

Laboratory infections usually occur when the parasites contact mucous membranes or broken skin, or are accidentally injected via needlestick injuries, but aerosol transmission might be possible in this setting.

Incubation period

In humans, the incubation period is usually at least 5 to 14 days after exposure to triatomine insect feces, and 20 to 40 days after infection by blood transfusion.

Many people do not become symptomatic until the chronic stage, which can occur 5 to 40 years after infection.

Acute phase

The acute phase is defined as the period during which the parasites can be found easily in the blood.

Many people, particularly adults, are asymptomatic during this stage.

The symptoms of the acute phase are highly variable and may include fever, headache, anorexia, malaise, myalgia, joint pain, weakness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and generalized or localized lymphadenopathy.

Edema, either generalized or localized to the face and/or lower extremities, occurs in some cases.

Sometimes, a chagoma (a localized painless induration) is seen where the parasite has entered through the skin.

If entry occurs via the ocular mucous membranes, there may be painless edema of one or occasionally both eyes, often accompanied by conjunctivitis and enlargement of the local lymph nodes. This syndrome, which is called Romaña’s sign, usually persists for 1 to 2 months.

Patients occasionally develop a rash, but this usually disappears within several days. In most cases, the clinical signs resolve within weeks to months without treatment; however, some acute cases can be fatal.

Indeterminate phase

The acute phase is usually followed by an asymptomatic period of varying length; this stage is called the indeterminate phase.

During the indeterminate phase, the parasites disappear from the blood. Although estimates vary, approximately 70% to 90% of the patients in the indeterminate phase never become symptomatic.

Most of the remaining patients enter the chronic phase after 5 to 15 years, but in a few patients, the indeterminate phase can last as long as 40 years.

Chronic phase

The chronic phase is typically represented by organ failure, usually of the heart or digestive system.

Heart disease, the most common form of chronic Chagas disease, may be characterized by arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities, cardiac failure, apical aneurisms, embolic disease including stroke or pulmonary embolism, and sudden death. Signs of isolated left heart failure may occur first.

Digestive system abnormalities lead to megaesophagus and/or megacolon, which can occur concurrently with heart disease. The symptoms of megaesophagus may include pain during swallowing, excessive salivation, regurgitation and chest pain.

In severe cases, there may be weight loss or cachexia, and the esophagus may rupture. The symptoms of megacolon include severe constipation, which can last for a few days to months, and abdominal pain that is often associated with episodes of constipation.

Patients with Chagas disease also have an increased chance of developing gastric ulcers or chronic gastritis, due to abnormalities in the stomach.

Immunocompromised people can be severely affected

Women who are infected with T. cruzi can give birth to infected children. Congenital infections may occur during any of the woman’s pregnancies, whether she is symptomatic or not. In congenitally infected infants, the most common symptoms are premature birth, hepatosplenomegaly, meningoencephalitis, changes in the retina and signs of acute myocarditis/ cardiac insufficiency. Transplacental infections are also associated with abortions.

Patients with AIDS suffer a more severe form of the disease with a high percentage of neurological and cardiac signs. Many of these patients develop T. cruzi brain abscesses, which are not seen in immunocompetent patients. HIV-infected individuals and others who are immunosuppressed, including those who receive organ transplants, are at risk for reactivation of T. cruzi replication.

Chagas disease can be diagnosed by

- Microscopy

- Isolation of the parasite

- Serology

- Molecular techniques

Light microscopy can sometimes detect T. cruzi in Giemsa or Wright stained samples of blood, cerebrospinal fluid or tissues. T. cruzi can be found in the heart, skeletal and smooth muscle cells, and the glial cells of the nervous system. It sometimes occurs in chagomas. In immuno-compromised patients, parasites may also be detected in atypical sites such as the pericardial fluid, bone marrow, brain, skin and lymph nodes. Active parasitemia is much more likely to be found during the acute than the chronic stage.

T. cruzi can be cultured from heparinized blood samples or tissues. Various specialized media including liver infusion tryptose medium or Novy-MacNeal-Nicolle medium, as well as Vero cell lines can be used. Culture may take 1 to 6 months.

Serology is most often used to diagnose chronic infections. Commonly used serological tests in humans include indirect immunofluorescence (IFA), hemagglutination and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). Other tests including radioimmunoprecipitation and complement fixation may also be used. Cross-reactions can occur with other parasites, particularly Leishmania species.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques can be used for diagnosis. Immunoblotting (Western blotting) is another option.

.png)

Acute Chagas disease can be treated with antiparasitic drugs. In the U.S., drugs may be available only under an Investigational New Drug protocol from the CDC Drug Service.

Treatment of acute or congenital cases is recommended to prevent the development of chronic disease.

Antiparasitic drugs are less effective in the indeterminate and chronic stages, and treatment recommendations may vary with the age of the patient and other factors.

There are significant side effects with these drugs, which must be given long term. In the chronic stage, treatment of cardiomyopathy is mainly symptomatic and similar to the treatment of other causes of heart disease. A pacemaker may be necessary, and a heart transplant can be considered.

Examples of drugs include benznidazole and nifurtimox.

Surgery, balloon dilation of the gastroesophageal junction and/or symptomatic relief may be used for chagasic megaesophagus or megacolon.

The morbidity and mortality rates vary with the stage of the disease.

Approximately 5% of people infected with T. cruzi develop acute symptoms. Estimates of the case fatality rate for acute Chagas disease range from less than 5% to approximately 8%; among immunologically competent individuals; deaths occur mainly in young children with acute myocarditis or meningoencephalitis.

The CDC estimates that 20 to 30% of humans infected with T. cruzi eventually develop chronic disease; estimates from other sources vary from 10% to 50%. The reason for the progression of disease in some patients but not others is unknown. It may be related to host genetic factors, the dose of the parasites, the number of inoculations, the strain of the parasite, and immunological or nutritional factors.

Cardiac disease is often fatal. Occasionally, deaths are also caused by volvulus of a dilated sigmoid megacolon.

Currently, states are not required by federal law to report cases of Chagas disease. However, Chagas disease is reportable by state mandate in Arizona, Massachusetts, and Tennessee.

At this time, there are no plans to add Chagas disease to the list of diseases which are nationally notifiable.

Prevention in Humans

Contact with triatomine insects should be prevented; they usually feed at night and withdraw to their hiding places in daylight. In endemic areas, houses can be improved by plastering walls, improving flooring and taking other measures to remove the cracks where these insects hide.

Triatomine insects are often found in basements, which should be avoided. Sleeping inside a screened area, under a permethrin-impregnated bed net, or in an air-conditioned room is safest. Bed nets should be tucked tightly under the mattress before dusk.

Animal pens and storage areas should be kept away from homes.

Regular spraying of insecticides in and around houses can reduce the number of insects, and in some cases, eliminate them.

Foods that might be contaminated should be cooked.

Since 1991, the Pan American Health Organization and the World Health Organization have run a joint program to eliminate T. infestans, the most important vector for Chagas disease in humans. This program has decreased the distribution of this insect by more than 80%, although foci can still be found in some regions.

Blood and organ donors should be screened to prevent transmission by these routes. In the U.S., transfused blood has been screened for Chagas disease since 2007.

Pregnant women can be tested to identify cases where congenital transmission may occur, and the infant should be monitored and treated if necessary.

People in occupational risk groups should take additional precautions.

- Veterinarians and technicians should protect their skin and mucous membranes from contamination with parasites in blood or tissues. This includes using gloves and/or other barriers while drawing blood samples from T. cruzi-infected animals, taking care of IV catheters or performing other invasive procedures.

- Needles and other “sharps” must be handled and disposed of properly to prevent needlestick injuries.

- Individuals who work with wildlife and hunters should also take precautions, especially when handling blood and tissues. Laboratory personnel should use appropriate personal protective equipment, including gloves and eye protection, while processing blood samples, cultures or infected insects.

- If an accidental exposure occurs, the site should be disinfected immediately if possible, and antiparasitic drugs may be given prophylactically.

Travelers to areas where Chagas disease is common should wear thick clothing that covers as much of the body as possible; heavy long-sleeved shirts, long pants, socks and shoes are recommended. Sleeping in sub-standard housing should, if possible, be avoided.

Vaccines are not available for humans; however, precautions can be taken to reduce the risk of infection, particularly in countries where the prevalence of Chagas disease is high.

Prevention in Animals

Dogs and cats should not be allowed to eat tissues from potentially infected wild animals. Strict indoor housing in well-constructed homes or other facilities reduces the risk of infection.

Housing animals indoors at night, when triatomine insects are active, may also be helpful. Residual insecticides sprayed regularly in kennels and surrounding structures may decrease the number of insect vectors.

In breeding kennels, testing bitches for T. cruzi-might also decrease the incidence of Chagas disease by reducing vertical transmission. No vaccines are available.

Practice Questions

Check how well you grasp the concepts by answering the following questions...

- This content is not available yet.

Send your comments, corrections, explanations/clarifications and requests/suggestions