What You Will Learn

After reading this note, you should be able to...

- This content is not available yet.

Definition

Suture is a medical device used to hold body tissues together after an injury or incision until such a time as the natural healing process is sufficiently well established.

Overview

- For centuries, various suture materials were used. Sutures made of plant or animal materials and needles of bones and metals.

- The early sutures were made from biological materials like catgut and silk sutures. Most sutures now are synthetic either absorbable or non-absorbable.

- Over the years, a number of different thread materials, needle shapes, and sizes have been developed. Surgical knots are used to secure the sutures.

- History: Egypt 3000BC, Mummy 1100BC, Shushruta 500BC, Sterile catgut in 1906, Catgut banned in Europe/Japan

Suturing has been used throughout the ages to help human tissues heal, by approximating the wound edges and reducing the dead space.

Historically, plant or animal fibers were used for thread and the needles were shaped from animal bone or bits of metal. In the modern era, sterilized sutures and needles have mostly replaced these materials but the essential principles remain the same.

Sutures, and the needles on which they are mounted, are available in a multitude of shapes, sizes, and materials. Each material has its own unique properties, benefits, and disadvantages; hence, they are tailored according to the specific requirements of the wound. When closing wounds with sutures, it is important to understand these properties to achieve the best possible healing result.

- The ideal suture should allow the healing tissue to recover sufficiently to keep the wound closed together once they are removed or absorbed.

- The time it takes for a tissue to no longer require support from sutures will vary depending on tissue type:

- Days: Muscle, subcutaneous tissue, or skin

- Weeks to Months: Fascia or tendon

- Months to Never: Vascular prosthesis

- It is worth noting that regardless of suture composition, the body will react to any suture as a foreign body, producing a foreign body reaction to varying degrees.

- Broadly classified into absorbable or non-absorbable materials

- Further sub-classified into synthetic or natural sutures, and monofilament or multifilament sutures.

The ideal suture is the smallest possible to:

- Produce uniform tensile strength

- Securely hold the wound for the required time for healing, then be absorbed.

- It should be predictable, easy to handle, produce minimal reaction, and knot securely.

The suture type chosen varies much depending on the clinical scenario. For example, as a rough guide, a mass closure of a midline laparotomy may warrant the use of PDS, a vascular anastomosis will probably require prolene, a hand-sewn bowel anastomosis may need vicryl, and securing a drain may need a silk suture.

Absorbable Sutures

- Absorbable sutures are broken down by the body via enzymatic reactions or hydrolysis. The time in which this absorption takes place varies between materials, location of suture, and patient factors.

- Absorbable sutures are commonly used for deep tissues and tissues that heal rapidly; as a result, they may be used in small bowel anastomosis, suturing in the urinary or biliary tracts, or tying off small vessels near the skin.

- Sutures lose significant tensile strength generally within 60 days of being in the tissue

- Note: period refers to tensile strength, not disappearance from tissue

- Suture is broken down by hydrolysis and phagocytosis

- Rapidly absorbable: catgut, vicryl, polyglycolic (Dexon)

- Slowly absorbable: PDS, maxon

- Dehiscence results if suture loses strength before tissue regains its strength

- For the more commonly used absorbable sutures, complete absorption times will vary:

- Vicryl rapide = 42 days

- Vicryl = 60 days

- Monocryl = ~100 days

- PDS = ~200 days

Non-absorbable Materials

- Non-absorbable sutures are used to provide long-term tissue support, remaining walled-off by the body’s inflammatory processes until removed manually if required.

- Uses include for tissues that heal slowly, such as fascia or tendons, closure of abdominal wall, or vascular anastomoses.

- Sutures maintain their tensile strength in tissue generally for at least 60 days

- Some lose strength over a prolonged period while others maintain their original strength and are surrounded by fibrous tissue

- Monofilament sutures are preferred

- Avoid burying multifilament sutures, especially in lumens (e.g., gallbladder, bladder), and in infected or contaminated sites

Classification of Suture Materials by Raw Origin

- Natural: made of natural fibers (e.g., silk or catgut). They are less frequently used, as they tend to provoke a greater tissue reaction. However, suturing silk is still utilized regularly in the securing of surgical drains.

- Synthetic: comprised of man-made materials (e.g., PDS or nylon). They tend to be more predictable than natural sutures, particularly in their loss of tensile strength and absorption.

- Natural Sutures:

- Made of natural fibers

- Can be absorbable or non-absorbable

- Elicit more tissue reaction

- Varied rates of absorption and tensile strength loss

- Examples: catgut, silk, cotton

- Synthetic Sutures:

- Man-made materials

- Can be absorbable or non-absorbable

- Less tissue reaction

- Predictable rates of absorption and tensile strength loss

- Examples: polyglactin, nylon, PDS

Classification of Suture Materials by Structure

- Monofilament suture: a single-stranded filament suture (e.g., nylon, PDS*, or prolene). They have a lower infection risk but also have poor knot security and ease of handling.

- Multifilament suture: made of several filaments that are twisted together (e.g., braided silk or vicryl). They handle easier and hold their shape for good knot security, yet can harbor infections.

Monofilament versus multifilament

Monofilament suture is made of a single strand. This structure is relatively more resistant to harboring microorganisms. Monofilament sutures exert less resistance to passage through tissue than multifilament suture. This type of suture handles and ties well.

Multifilament suture is composed of several filaments twisted or braided together. Multifilament suture generally has greater tensile strength and better pliability and flexibility than monofilament suture. Because multifilament materials have increased capillarity, the increased absorption of fluid may act as a tract for the introduction of pathogens.

| Suture Types | Generic Structure | Classification | Representative Product/Brand |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catgut | Collagen from animal intestines | Natural, absorbable, twisted multifilament (monofilament) | Surgical Gut, Chromic Gut |

| Silk | Fibroin from silkworm Bombyx mori | Natural, non-absorbable, braid multifilament | Perma-Head, Softsilk |

| Polypropylene | Isotactic crystalline stereoisomer of PP | Synthetic, non-absorbable, monofilament | Prolene, Surgipro |

| Polyamide | Nylon 6 and nylon 6,6 | Synthetic, non-absorbable, monofilament | Ethilon, Dermalon |

| Stainless steel | 316L (low carbon) stainless steel alloy | Metal, non-absorbable, mono and multifilament | Ethisteel, Flexon |

| Polyglycolic acid/Polylactic acid | 90% PGA, 10% PLA | Synthetic, absorbable, braided multifilament | Vicryl, Vicryl Rapide |

| Polydioxanone | Polyester p-dioxanone | Synthetic, absorbable, monofilament | PDS II |

| Polyglycolic acid/Polytrimethylene carbonate | Copolymer of glycolic acid and trimethylene carbonate | Synthetic, absorbable, monofilament | Maxon |

- The diameter of the suture will affect its handling properties and tensile strength. The larger the size ascribed to the suture, the smaller the diameter is, for example, a 7-0 suture is smaller than a 4-0 suture.

- When choosing suture size, the smallest size possible should be chosen, taking into account the natural strength of the tissue.

- Select the smallest suture size possible to support the tissue

- If the suture is too fine, it may break before healing, leading to dehiscence

- If the suture is too large, the tissue may conform to the suture, leading to foreign body reaction

- The ideal surgical needle should be:

- Rigid enough to resist distortion

- Flexible enough to bend before breaking

- As slim as possible to minimize trauma

- Sharp enough to penetrate tissue with minimal resistance

- Stable within a needle holder to permit accurate placement

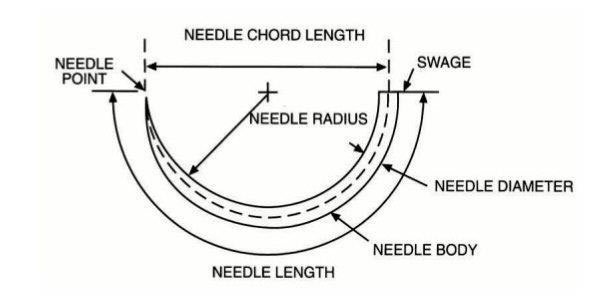

- Commonly, surgical needles are made from stainless steel and are composed of:

- The swaged end connects the needle to the suture

- The needle body or shaft is the region grasped by the needle holder. Needle bodies can be round, cutting, or reverse cutting:

- Round bodied needles are used in friable tissue such as liver and kidney

- Cutting needles are triangular in shape, have 3 cutting edges to penetrate tough tissue such as the skin and sternum, and have a cutting surface on the concave edge

- Reverse cutting needles have a cutting surface on the convex edge, ideal for tough tissue such as tendon or subcuticular sutures, and have a reduced risk of cutting through tissue

- The needle point acts to pierce the tissue, beginning at the maximal point of the body and running to the end of the needle, and can be either sharp or blunt:

- Blunt needles are used for abdominal wall closure and in friable tissue, potentially reducing the risk of blood-borne virus infection from needlestick injuries

- Sharp needles pierce and spread tissues with minimal cutting, used in areas where leakage must be prevented

- The needle shape varies in curvature and is described as the proportion of a circle completed – the ¼, ⅜, ½, and ⅝ are the most common curvatures used. Different curvatures are required depending on the access to the area to suture.

An ideal suture should possess the following characteristics:

- Easy to handle: The suture should be easy for the surgeon to manipulate and tie securely without excessive effort.

- Minimal tissue reaction: It should provoke minimal inflammatory response or tissue irritation to promote optimal wound healing.

- Antimicrobial properties: Ideally, the suture material should possess antimicrobial properties to inhibit bacterial growth and reduce the risk of wound infection.

- Secure holding: The suture should hold the wound edges firmly together to prevent dehiscence (wound opening) and promote proper wound healing.

- Supportive: It should provide adequate support to the incision or wound during the healing process, especially in tissues under tension.

- Conformable: The suture should conform to the contours of the tissue to ensure even distribution of tension and minimize tissue trauma.

- Biodegradable or absorbable: The suture material should gradually degrade or be absorbed by the body over time, eliminating the need for removal and reducing the risk of complications.

- Cost-effective: It should be economical and cost-effective for healthcare providers while maintaining high quality and performance.

- Sterilization compatibility: The suture material should be easy to sterilize using standard sterilization methods to ensure safety and sterility during surgical procedures.

No single suture is ideal: Despite advancements in suture materials, no single suture material can fulfill all ideal characteristics, and the choice of suture type depends on various factors, including the type of tissue being sutured, the location of the wound, and individual patient factors.

Practice Questions

Check how well you grasp the concepts by answering the following questions...

- This content is not available yet.

Send your comments, corrections, explanations/clarifications and requests/suggestions