What You Will Learn

After reading this note, you should be able to...

- This content is not available yet.

Note Summary

This content is not available yet.

closeClick here to read a summary

- The link between psychiatric and physical disorders is well established.

- Depression is more common in people with chronic illnesses (e.g., angina, asthma, arthritis, and diabetes).

- Comorbidity of depression with these chronic conditions produces significantly greater decrements in health than from one or more of the cases of the chronic disease.

- The additive effect is particularly amplified in the case of depression comorbid with diabetes.

- Depression delays recovery from physical illness and increases the risk of death following myocardial infarction and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Reasons for the High Prevalence of Psychiatric Illness Among Medical Patients

- Pre-existing psychiatric illness contributing to the development of physical illness.

- Psychological reaction to physical illness.

- Organic effects of illness on mental function (e.g., Delirium, dementia, organic affective disorders).

- The effects of medically prescribed drugs on mental function and behavior.

- Medically unexplained symptoms that mask underlying psychiatric illness.

- Alcohol and drug misuse.

Pre-existing Psychiatric Illness

Pre-existing Psychiatric Illness Contributing to the Development of Physical Illness

People with psychiatric illness are more likely than the general population to develop one or more physical disorders.

Common psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders predispose to obesity and its multiple complications, such as diabetes, osteoarthritis, hypertension, and coronary artery disease.

Patients with affective disorders have increased mortality from infections and from neurological, circulatory, and respiratory disorders.

Psychological Reaction to Physical Illness

- Patients become emotionally distressed when they develop physical illness during the early stages when the diagnosis and required treatment may not have been clearly defined.

- Most patients cope emotionally in an adaptive manner, modifying their lifestyle in accordance with the severity of symptoms and the demands of treatments.

- A significant minority develops recognizable psychiatric disorders—a mixture of anxiety and depression—which could take the form of an adjustment disorder. This may resolve within a few weeks if the prognosis is recognized as being favorable.

Note: In some cases, symptoms of anxiety and depression do not resolve even though there may be complete physical recovery. Prolonged anxiety, phobic, or depressive reactions may then develop.

Diagnosing Depressive Illness in Physical Illness

Attention should be placed on psychological symptoms such as anhedonia, hopelessness, and suicidal thoughts. Less emphasis should be placed on somatic symptoms such as anorexia, weight loss, and fatigue, all of which might be explained by the underlying physical disease.

- Once depressive symptoms are elicited, an assessment of suicidal risk becomes essential.

- Patients considered to be at high risk will need special care and consideration.

Acute Psychiatric Reaction

A rare complication in people of paranoid disposition. It takes the form of a systemized delusional experience, nearly always with persecutory content, occurring in clear consciousness (consciousness is impaired in delirium).

- Most likely to develop in coronary care or intensive care units.

- Unfamiliarity with the high technology environment could be responsible.

Symptoms usually resolve if the patient can be transferred to an environment perceived as less threatening.

PTSD

Explore for symptoms of PTSD in patients admitted to the hospital following trauma, such as sleep disturbances, increased arousal, and phobic avoidance.

If the stay is brief, the characteristic symptoms may not develop during the admission but may become apparent during the weeks following discharge from the hospital.

Organic Effects of Physical Illness

- Delirium

- Dementia

- Organic Mood Disorders

Depression and mania may be the first manifestation of an underlying physical illness. Presentation is characterized by the essential features of depression or mania. Symptoms are induced by disruption of cerebral anatomical pathways or physiological systems.

- Change in mood follows the presumed physical illness and not emotional reaction to it.

- Circumstances or conditions that could raise suspicion for an underlying physical cause for mood changes are:

- Depression present for the first time in middle age or later.

- There is no understandable psychosocial etiology.

- There is no family history of mood disorder.

- The patient has a stable premorbid personality.

Potential Causes of Organic Mood Disorders

- Neurological:

- Stroke

- Multiple sclerosis

- Parkinson's disease

- Traumatic brain damage

- Tumors

- Degenerative disorders

- Endocrine:

- Hypothyroidism

- Hyperthyroidism

- Cushing's disease

- Addison's disease

- Hyperparathyroidism

- Hypoparathyroidism

- Collagen Diseases:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Infections:

- Viral encephalitis

- Cerebral syphilis

- HIV

- Systemic infections (e.g., Pneumonia, UTI)

- Malignant Disease:

- Cerebral tumor (primary or secondary)

- Non-metastatic effects of distant tumor

Organic Anxiety Disorder

Anxiety may be the first manifestation of physical illness. The most likely causes are:

- Hyperthyroidism

- Paroxysmal cardiac arrhythmias

- Hypoglycemia

- Temporal lobe epilepsy

Effects of Medically Prescribed Drugs

Effects of Medically Prescribed Drugs on Mental Function and Behavior

- Whenever psychological symptoms are found in a medical or surgical patient, the possibility should be considered that they have been induced by medication.

Examples:

- Delirium:

- CNS depressants e.g., hypnotic withdrawal, sedatives, alcohol, antidepressants, neuroleptics, anticonvulsants, antihistamines, anticholinergics, beta-blockers, digoxin, cimetidine

- Psychotic symptoms:

- Appetite suppressants

- Sympathomimetic drugs

- Beta-blockers

- Corticosteroids

- L-dopa

- Indomethacin

- Mood Disorders:

(a) Depression:

- Antihypertensive drugs

- Oral contraceptives

- Neuroleptics

- Anticonvulsants

- Corticosteroids

- L-dopa

- Calcium-channel blockers

(b) Elation (Hypomania):

- Antidepressants

- Corticosteroids

- Anticholinergic drugs

- Isoniazid

- Behavioural Disturbance:

- Benzodiazepines

- Neuroleptics

Medically Unexplained Symptoms

An unsatisfactory term commonly used to describe the presentation of psychiatric illness with somatic symptoms for which no adequate underlying medical explanation can be found.

Other terms used:

- Somatisation syndrome

- Functional somatic syndrome

A small percentage of patients with medically unexplained symptoms are admitted to medical wards.

Alcohol and Drug Misuse

This is very common among medical patients. Hospital admission affords a good opportunity to detect these problems during history taking. This may be supplemented by using a brief questionnaire.

Main therapeutic involvement includes managing withdrawal syndromes from alcohol, opiates, and benzodiazepines.

An aspect of psychiatry (Liaison psychiatry) that is concerned with normal psychological reactions to cancers and cancer treatments, as well as addressing psychiatric reaction disorders among people with cancer.

Psychological and psychiatric problems associated with specific cancers and cancer treatments:

- Coping with cancer is a challenge for anyone. Patients with cancer can be considered under five headings - the five Ds - death, dependence, disfigurement, disruption, and disability.

- The type and stage of the cancer determine the relevance and importance of each of the Ds.

The Five Stages of Grief

The Kübler-Ross model, commonly known as the five stages of grief, was first introduced by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her 1969 book, "On Death and Dying."

- Denial: "I feel fine."; "This can't be happening, not to me." Denial is usually only a temporary defense for the individual. This feeling is generally replaced with heightened awareness of situations and individuals that will be left behind after death.

- Anger: "Why me? It's not fair!"; "How can this happen to me?"; "Who is to blame?" Once in the second stage, the individual recognizes that denial cannot continue. Because of anger, the person is very difficult to care for due to misplaced feelings of rage and envy. Any individual that symbolizes life or energy is subject to projected resentment and jealousy.

- Bargaining: "Just let me live to see my children graduate."; "I'll do anything for a few more years."; "I will give my life savings if..." The third stage involves the hope that the individual can somehow postpone or delay death. Usually, the negotiation for an extended life is made with a higher power in exchange for a reformed lifestyle. Psychologically, the individual is saying, "I understand I will die, but if I could just have more time..."

- Depression: "I'm so sad, why bother with anything?"; "I'm going to die... What's the point?"; "I miss my loved one, why go on?" During the fourth stage, the dying person begins to understand the certainty of death. Because of this, the individual may become silent, refuse visitors, and spend much of the time crying and grieving. This process allows the dying person to disconnect oneself from things of love and affection. It is not recommended to attempt to cheer up an individual who is in this stage. It is an important time for grieving that must be processed.

- Acceptance: "It's going to be okay."; "I can't fight it, I may as well prepare for it." In this last stage, the individual begins to come to terms with their mortality or that of their loved one.

Kübler-Ross originally applied these stages to people suffering from terminal illness, later to any form of catastrophic personal loss (job, income, freedom). This may also include significant life events such as the death of a loved one, divorce, drug addiction, the onset of a disease or chronic illness, an infertility diagnosis, as well as many tragedies and disasters.

Kübler-Ross claimed these steps do not necessarily come in the order noted above, nor are all steps experienced by all patients, though she stated a person will always experience at least two. Often, people will experience several stages in a "roller coaster" effect—switching between two or more stages, returning to one or more several times before working through it.

Significantly, people experiencing the stages should not force the process. The grief process is highly personal and should not be rushed, nor lengthened, on the basis of an individual's imposed time frame or opinion. One should merely be aware that the stages will be worked through and the ultimate stage of "Acceptance" will be reached.

However, there are individuals who struggle with death until the end. Some psychologists believe that the harder a person fights death, the more likely they are to stay in the denial stage. If this is the case, it is possible the ill person will have more difficulty dying in a dignified way. Other psychologists state that not confronting death until the end is adaptive for some people. Those who experience problems working through the stages should consider professional grief counseling or support groups.

Breast Cancer

It can be a life-threatening condition. Women with early breast cancer are made aware of 95-98% 5-year survival rates with treatment.

- This prognostic information may alleviate anxiety in some patients, but the uncertainty of the 2-5% risk to life is almost unbearable.

Coping with uncertainty could be a central psychological issue.

Surgical Treatment for Breast Cancer:

- Lumpectomy

- Axillary lymph node removal

- Total mastectomy

- Various breast reconstruction techniques

These procedures are mutilating and directly affect body image and psychosexual function. For example, loss of nipple after breast-conserving surgery for Paget's disease removes what may have been an important source of sexual arousal and alters body image.

Chemotherapy:

Usually causes hair loss, fatigue, and vomiting. Fertility is often lost.

Hormonal Treatment (such as tamoxifen):

Provokes an early menopause and causes weight gain and night sweats.

Overtime, many patients with breast cancer come to see it as a long-term medical condition characterized by persistent lymphedema of the arm, vaginal dryness, weight gain, and frightening annual reviews. It is not straightforward to achieve or resume such social roles as worker, lover, or mother in the face of these experiences.

Factors that determine how women cope psychologically:

- Young women with pre-existing body image problems or histories of negative sexual experiences are particularly distressed.

- Breast reconstruction gives better psychosexual outcomes than mastectomy alone.

- Patients with breast cancer and a history of psychiatric disorder experience more psychiatric symptoms of anxiety and depression than those with better premorbid mental health.

Head and Neck Cancer

Commonly seen in older men with a long history of smoking and alcohol misuse (alcohol and tobacco act synergistically as carcinogens).

- Male:female ratio = 3:1.

- Prior to cancer diagnosis, they are socially isolated and have substance dependence. They have premorbid psychosocial problems.

- Disfigurement and dysfunction are the most prominent problems.

Head and neck cancer and the results of their treatment can be a huge assault on simple pleasures such as eating, tasting, speaking, kissing, breathing, feeling safe alone, and self-worth.

Chewing, swallowing, or even sealing the lips to prevent drooling of saliva can be impaired.

Dysarthria is a barrier to social contact, functions as a loss event, and can be an obstacle to any talking treatment to reduce stress.

Sexual contact, kissing, and even eye-gazing by partners are reduced.

Anxiety peaks peri-operatively, depression peaks around 3 months post-operatively.

At 3-year follow-up, 40% of patients with head and neck cancer have depression (much higher than the 9-25% prevalence of depression in patients with cancer generally).

Head & Neck (& Lung) cancer account for 50% of all deaths by suicide in people with cancer. Risk factors for completed suicide include the following:

- Male

- Older age

- Living alone

- Alcohol dependence

- Poor social network in addition to impaired quality of life caused by the cancer itself

Cancer Treatment

Chemotherapy often causes alopecia and infertility. Infertility and both can be distressing.

Some patients develop secondary phobia to chemotherapy due to bad experiences with uncontrolled nausea and vomiting after treatment.

Corticosteroids can cause psychosis, for example. The most severe form will cause some mania symptoms with clouding of consciousness.

Certain chemotherapy agents, e.g., 5-chlorouracil which causes cerebellar ataxia and delirium, methotrexate can cause delayed leukoencephalopathy, alpha interferon can cause depression, irritability, and impaired intellectual function.

Radiotherapy causes fatigue and can persist for months after treatment ends.

Causes of Radiotherapy-Associated Psychiatric Symptoms

- The use of high dose dexamethasone as an adjunct to radiotherapy of the CNS. Corticosteroids cause elation of mood and psychosis.

- Radiotherapy of the head, neck, and chest could lead to hypothyroidism due to unavoidable irradiation of the thyroid gland, and this can present with psychiatric symptoms, notably depressive symptoms.

Breaking Bad News

Communication skills relating to prognosis, death, and dying ("Breaking bad news of diagnosis").

Why "Breaking Bad News" May Be an Unfortunate Label?

There should be more emphasis on sharing information about what can be offered to help and treat, rather than announcing the bad news itself.

Preparation for Important Information-Giving

- A quiet, comfortable, private setting without interruption or rushing.

- Find out what they already know, but don't drag this out.

- Give a warning shot that there is bad news.

- Break the news in plain language at a place the patient can manage.

- Pause to allow some reaction and respond empathically to this.

- Invite questions and offer a follow-up opportunity for questions on another day.

- Convey a clear message about what care is on offer in order to instill hope.

- Tell colleagues what was said and record it in the medical note.

- Convey that it is possible to discuss issues about palliation and the process of dying without too much distress or embarrassment for either doctor or patient.

Acknowledgement of Terminal Disease and Realistic Hope

Acknowledgement of terminal disease should be combined with realistic hope of good palliation (e.g., "The team will stay alongside you to the very end").

Encouraging Discussion and Support

- Discussion of any specific questions or fears the patient has about mode of death and process of dying should be encouraged.

- Where does the patient wish to die and how can this be supported?

Review of Practical and Personal Preparations

There should be a review of practical and more personal preparations for death. For example, financial and legal arrangements, final trips, or attempts at reparation of relationships may need attention.

This kind of discussion can draw on the principles of Chochinov et al's (2005) dignity therapy.

Dignity Therapy

- Terminally ill patients are invited to state roles or issues that define them, review the major accomplishments in their life, and make statements to loved ones concerning the past and future.

- A written document is generated which is then shared with family members.

- Overall, 70% of patients found this increased their dignity and sense of meaning approaching death.

Typical Prompt Questions for Terminally Ill Patients

- Are there specific things you would want your family to know or remember about you?

- What were the most important accomplishments in your life and why did they matter to you?

- Are there particular things you feel still need to be said to your loved ones?

- What have you learned about life that you would want to pass on?

Grief and Bereavements

Typical Reactions to Impending Death

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross's stages of grief (a psychiatrist and thanatologist)

- Shock and Denial

- Shock and disbelief

- Anger

- Painful dejection, despair, helplessness, protest, and anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

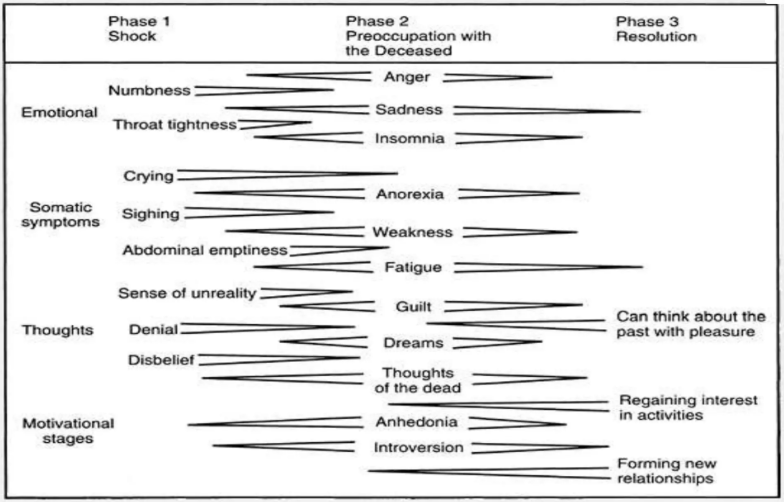

Classic Account of Stages of Grief

- Description of various stages rather than consecutive stages seen in bereavement.

- Individual patients will experience each of these reactions (and others) in varying degrees, combinations, and sequences.

- Grief - is the psychological response to loss e.g. body part or function, independence, affection.

Somatic Symptoms

- Insomnia, anorexia and weight loss, tightness in the throat, chest or abdomen, and fatigue.

The length and intensity of the phases of shock and preoccupation are affected by the suddenness of the death:

- When there has been no warning - period of shock and disbelief is prolonged and intense.

- When death has been long expected - much of the mourning process may occur while the loved one is still alive, leaving an anticlimactic feeling after the death.

Normal Grief Progression

- In normal grief, the intensity of symptoms gradually abates, so that by 1 month after death, the mourner should be able to sleep, eat, and function adequately at work and at home.

- Crying and feelings of longing and emptiness do not disappear, but are less intrusive.

- By 6 to 12 months, most normal life activities will have been gradually resumed.

- For major losses, the grieving process continues throughout life, with the reappearance of the symptoms of grief on anniversaries of the death or other significant dates, e.g., wedding anniversaries, birthdays.

"Normal" Reactions

- There is a wide range of variability - there is not a "right way" to mourn applicable to everyone.

- The type or cause of death can greatly influence the character of grief and mourning.

- Grief is least likely to be complicated following anticipated death of elderly patients with disease without social stigma.

- Those mourning a victim of suicide or homicide usually have more anger, angst, religious conflicts, and guilt.

- Grief following death from HIV/AIDS may be complicated by fear, shame, hopelessness, sexual conflicts, recrimination, isolation, and stigma.

- Grief and mourning also occur following losses other than deaths, e.g., loss of body part (e.g., amputation, mastectomy), loss of body functions (e.g., blindness, paraplegia).

- Caregivers for a patient with Alzheimer's disease experience grief long before the patient's death because "his personality died long before he did."

- Even the loss of time may produce grief, e.g., an individual who overcame long-standing abuse and then in abstinence feels the full weight of wasted years.

Developmental Changes in Grief

- Although young children do not fully comprehend death's permanence, they certainly experience grief.

- Sleep disturbance, developmental regression (e.g., enuresis), behavior problems, and magical thinking are common.

- Older children and adolescents have a fuller understanding of death; decline in school performance, strained peer relationships, sleep disturbance (especially hypersomnia), and acting out are common.

- Younger adults have full intellectual comprehension of death but denial of death's personal relevance is typical.

Distinguishing Grief from Depression

Many psychological, social, and vegetative symptoms of depression also occur in grief.

| Grief | Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| time course | Severe symptoms 1-2 months | Longer |

| Suicidal ideation | Usually not present | Often present |

| Psychotic symptoms | Only transient visions or voice of the deceased | May have sustained depressive delusion |

| Emotional symptoms | Pangs interspersed with normal feelings | Continuous pervasive depressed mood |

| Self blame | Related to deceased | Focused on self |

| Response to support and ventilation | Improved overtime | No change or worsening |

Pathological Grief

In some individuals, grief and mourning do not follow the normal course.

- Grieving may become too intense or last too long; be absent, delayed, or distorted; or result in chronic complications.

- Grief that is too intense or prolonged exceeds the descriptions given of normal grief and can lead to an inability to function occupationally or socially for months.

Risk Factors for Pathological Grief

- Sudden or terrible deaths

- An ambivalent relationship with or excessive dependence on the deceased

- Traumatic losses earlier in life

- Social isolation

- Actual or imagined responsibility for "causing" the death

Absent or delayed grief occurs when the feelings of loss would be too overwhelming and so are repressed and denied.

- Such avoidance or repression of affect tends to result in the later onset of much more prolonged and distorted grief and in a higher risk for developing major depression, especially at later significant anniversaries.

NOTE:

- Physicians should be careful not to assume that grief is absent just because the individual is quiet and not affectively demonstrative.

Grief that is still symptomatic 1 year after the death is called chronic grief and occurs in approximately 10% of grief reactions.

- Some chronic persistence of active mourning is expectable after the closest losses (child, spouse, or life partner) but is considered abnormal if the mourner is unable to eventually resume full social and occupational functioning.

Causes of Chronic Grief

- Major unresolved conflicts with the deceased

- Overdependence

- Dysfunctional individual personalities

- Families characterized by chronic hostility

Chronic grief may evolve into a chronic depression; the boundary between them is not sharp.

Anticipatory Grief

Grief experienced in anticipation of death, sometimes long before the terminal phase of an illness, e.g., asymptomatic patients who learn they are HIV positive.

Anticipatory grief is not necessarily pathological but would be considered so when it promotes "giving up/given up" feelings or when the grief inappropriately interferes with adaptation to life, medical treatment, or planning for death.

Survival Guilt

A feeling that one does not deserve to have outlived the deceased and is especially common in those who have shared a traumatic experience with the deceased (e.g., same organ transplant program, airplane crash, or concentration camp).

It is normal in moderation but can become so pronounced that the survivors remain too guilty to ever return to full lives.

Complications of Prolonged Pathological Grief

- Major depression

- Substance dependency

- Hypochondriasis

- Increased morbidity and mortality from physical disease

The Physician's Role

The physician's role is to identify and help manage grief.

During the active phase of shock following a death, the physician can help the family accept the reality of the loss and provide a calm and reassuring presence that facilitates both the release of emotion and the planning necessary by those grieving.

- Patients frequently seek out their personal physicians when they are acutely suffering from grief and often focus on the somatic manifestations.

- The physician can explain the normal symptoms and process of grief and mourning and reassure patients that they are not "losing their minds."

- Family members who wish to see the body of the deceased in the hospital should be allowed (but never pressured) after the physician prepares them for distortion of appearance due to fatal disease, accident, or treatment.

Other Roles by the Physician:

- To address resuscitation status, advance directives, and related treatment issues with patients who are competent and with the families of patients who are not.

Besides the medical, ethical, and legal reasons for doing so, there are psychological benefits in making patients and families feel heard, respected, and able to contribute to terminal care.

- Discussion regarding the patient's wishes (e.g., organ donation) is another vital responsibility of physicians that may provide a source of hope and meaning in the face of senselessness and despair.

- Physicians should resist the temptation to sedate the individual suffering from acute grief because this tends to delay and prolong the mourning process.

- Antidepressants should not be prescribed for acute grief but rather reserved for a possible subsequent major depression. If insomnia is severe and does not spontaneously improve after several days, a brief course of a hypnotic may be prescribed, but extended use will be more harmful than beneficial.

Practice Questions

Check how well you grasp the concepts by answering the following questions...

- This content is not available yet.

Contributors

Jane Smith

She is not a real contributor.

John Doe

He is not a real contributor.

Send your comments, corrections, explanations/clarifications and requests/suggestions